Who was Pontius Pilate in the gospels?

What’s on this page?

Books about Pontius Pilate at the trial of Jesus.

Each of the gospel writers describes a slightly different man.

Who is right?

(The gospel of ) ‘John depicts Pilate, to whom Jesus was probably presented at short notice, as obliging and co-operative. He receives the chief priests early in the morning and, respectful of their purity concerns, meets them outside his residence. He politely inquires about the reason of their coming: ‘What accusation do you bring against this man?’

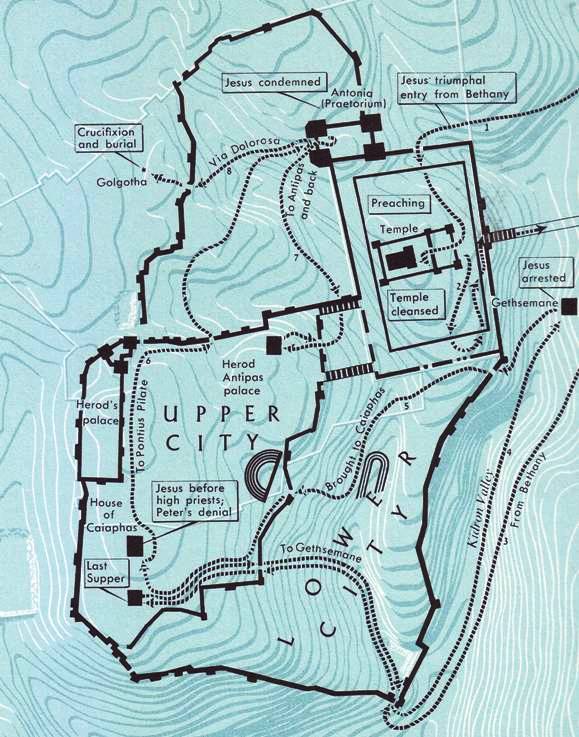

The Jewish delegation is described as cagey and in a hurry. No doubt they had many pressing matters to attend to in preparation for Passover. On that same afternoon the Temple was to become a giant slaughterhouse where priestly butchers would kill the thousands of Passover lambs for the Seder supper.

The Jewish delegation is described as cagey and in a hurry. No doubt they had many pressing matters to attend to in preparation for Passover. On that same afternoon the Temple was to become a giant slaughterhouse where priestly butchers would kill the thousands of Passover lambs for the Seder supper.

And there were the preparations for the solemn ritual of the fifteenth day of Nisan, which the chief priests had to conduct. lt consisted, Josephus tells us, of the sacrifice of two bulls, a ram and seven lambs to serve as burnt offerings, and a kid for sin offering (Jewish Antiquities 3:249).

So when Pilate asks about the charges against Jesus, he is curtly told that the accused is a wrong- doer; otherwise they would not have brought him here. To this Pilate sensibly retorts — and John’s Pilate is even more sensible than the Pilate of the Synoptics — that if the chief priests have nothing against him that concerns Rome, they should try him themselves according to Jewish law.

This reply gives rise to a totally unexpected riposte, which grotesquely amounts to a tutorial on Roman law given by the Jewish delegation to the Roman prefect. He should know that the Romans have deprived the Sanhedrin of the right to pronounce and execute capital sentences: ‘It is not lawful for us to put any man to death.’

John’s Pilate takes the reproof in his stride and meekly agrees to handle the case. So Jesus is ordered inside the palace, and the governor focuses his inquiry on Jesus’ kingship. Pilate is told that it is spiritual, not of this world, John informs us. Pilate then concludes that the priestly leaders are trying to involve him in a theological dispute about something he would have called their superstitio, and impresses on them that religious matters are outside his sphere of competence and that he can find no crime in Jesus in the political domain.

At this juncture the evangelists, like virtuoso wizards, present their readers with a surprise, the unforeseen legal custom (or fiction) of the privilegium paschale, or Passover amnesty.’

(The Passion, Geza Vermes, Penguin Books, 2005, p.55-57)

Pontius Pilate in the Four Gospels

MARK’S GOSPEL ‘Pilate in Mark’s gospel is not a weak governor, bowing to public pressure and the demands of the chief priesthood. Instead he is a skillful politician, manipulating the crowd to avoid a potentially difficult situation, and is a strong representative of imperial interests.

Although Mark clearly lays primary guilt for Jesus’ death upon the Jewish leadership, Pilate is not exonerated. He plays a vital part in the chain of events leading to the crucifixion and shares the guilt involved therein….

Although Mark clearly lays primary guilt for Jesus’ death upon the Jewish leadership, Pilate is not exonerated. He plays a vital part in the chain of events leading to the crucifixion and shares the guilt involved therein….

At his death not only is Jesus deserted by his closest supporters but the whole political world of first-century Palestine, both Jewish and Roman, have sided against him. The Jewish leadership have arrested and condemned him but Pilate sends Jesus for crucifixion.’

(Pontius Pilate in history and interpretation, Helen K. Bond & John Court, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p.117)

MATTHEW’S GOSPEL The Matthean Pilate plays a much less significant role within the Roman trial scene than the Markan Pilate. The governor attempts to show his innocence by publicly washing his hands and telling the Jewish crowd to see to Jesus’ execution themselves. Yet, like the chief priest in 27.4 who say the same words to Judas, Pilate is already too deeply implicated and cannot abdicate his responsibilities....

Whilst not so harsh and calculating as in Mark, the Matthean Pilate is none the less indifferent towards Jesus and willing to let the Jewish authorities have their way as long as he does not have to take the onus of responsibility.(p.136-7)

LUKE-ACTS In a drastic revision of his Markan source, Luke’s major apologetic purpose in 23:1-25 is to use Pilate as the official witness to Jesus’ innocence and to lay the blame for Jesus’ crucifixion first on the intrigues of the chief priests (vv. 1-12) and then on representatives of the whole Jewish nation (vv. 13-25).

This theme continues throughout Acts where Roman involvement nearly always follows Jewish plots. But once Pilate has three times declared Jesus innocent, Luke does not seem intent upon painting a glowing picture of Roman administration. In fact, quite the reverse. As C. H. Talbert notes, ‘Pilate appears more as an advocate who pleads Jesus’ case than as a judge presiding over an official hearing’.

He refuses to become involved with the charges and simply declares Jesus innocent. He does not want to bother with the case and seizes the opportunity to pass Jesus on to Herod. But Herod, who does question Jesus at length, albeit for self- interested motives, sees Jesus as no threat and returns him to the governor.

Eventually Pilate convicts a man whom he has declared innocent and releases a rebel and murderer because of the demand of the people. Bowing to Jewish pressure he undermines not only his own judgement but also that of Herod. In the end, Jewish mob pressure has triumphed over Roman justice. The weak Pilate has let down first himself and Herod, second the Roman administration he represents. (p.159)

JOHN’S GOSPEL The Johannine Pilate is far from a weak and vacillating governor. He takes the case seriously and examines Jesus but quickly realizes that he is no political threat to Rome. He seizes on the opportunity, however, not only to mock the prisoner but also to ridicule ‘the Jews’ and their messianic aspirations. Only once does he try to release Jesus and that is after the religious charge has been brought against him, a charge which the superstitious pagan finds alarming.

Brought back to reality by the political threats of ‘the Jews’, Pilate resumes his mockery. But this time he is on the judgement seat and he is guiding ‘the Jews’ in a certain direction.

Although he finds Jesus’ messianic claims ridiculous, he reasons that the prisoner is claiming some kind of kingship and could be dangerous in the crowded city at Passover time. By the final scene, Jesus is to be put to death.

But Pilate will exact a high price from ‘the Jews’. If they want Jesus executed, they must not only renounce their messianic hopes but unconditionally accept the sovereignty of Caesar. Only after this does Pilate hand Jesus over for crucifixion.

The Johannine Pilate, particularly in Scene 6, is reminiscent of the Roman governor in Mark’s account. In both the prefect is harsh and manipulative, mocking the people and goading them into rejecting their messianic beliefs….

In the proceedings before Pilate, all earthly authority is judged and found wanting by its response to Jesus. The contrast between the true, dignified, other-worldly kingship of Jesus and that of Caesar implies that each member of John’s community, constantly coming up against the might of imperial Rome, will always have to decide vis-a-vis the Empire whether Jesus is his king or whether Caesar is. (p.192-193)

The execution of Jesus was in all probability a routine crucifixion of a messianic agitator. Pilate, however, executed only the ring-leader and not his followers. This may betray a dislike of excessive violence, but also indicates prudence at the potentially volatile Passover season. Again, the governor appears to have worked closely with the Jewish hierarchy. (Pontius Pilate in history and interpretation, Helen K. Bond & John Court, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p.204)